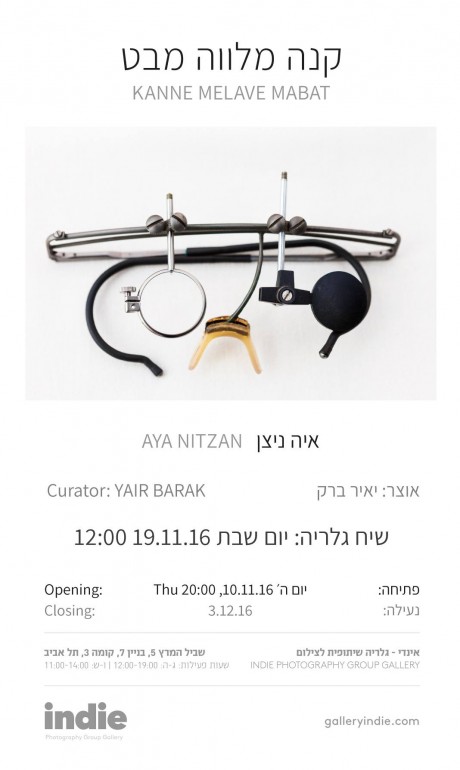

Aya Nitzan | Gun barrel tracks gaze

10.11.16-03.12.16

Curator | Yair Barak

At the center of Aya Nitzan’s show we are confronted by a projected image of smokestacks emitting smoke. The function of smokestacks is to dispose of industrial by-products; however, the smokestacks in Nitzan's image take in, rather than expel, like a person smoking continually. This "smoking gun" does not discharge - it accumulates.

The title of the show is "Gun barrel tracks gaze." This is a training direction used by instructors in military firing ranges. Technically, it means that the gun's sight must track the eye's gaze. Poetically, a different interpretation emerges: the gaze first, then violence commences. Any act of aggression begins with a stare. But the instruction conceals an inherent logical paradox. The barrel cannot track the gaze; it is an inanimate object. Only the gaze can track the barrel.

A similar, mythical pairing comes to mind, based on the Jewish ethos of "obey and listen." Just as the gaze precedes the barrel, consciousness precedes action. Conversely, the Jewish People's immediate, rash, unconditional acceptance of this directive, at the foot of Mount Sinai, symbolizes its blind adherence to the word of God. When doing precedes thinking and gun barrels precede the moral canon, injustice will find fertile ground.

Like the intaking stacks, which are unable to discharge the poison, the two young sharpshooters face each other, a boy and a girl holding Olympic competition rifles. The video shows an extended moment of preparation, aiming, and the promise of action – but there is none. The undischarged bullet remains in the barrel (which does not smoke). The rifles face each other. The closeness and the gender element suggest tension and a sense of intimacy, and, at the edge of the metaphor, unrequited passion.

A mature woman in a portrait is staring directly ahead. She is wearing a device on her eyes, which help her to close one eye effortlessly. Sharpshooters use these specialty glasses to focus their gaze on the target. The woman is the artist's mother. Mother and daughter establish a relationship of looks: the artist behind the camera shuts one eye; the mother returns a one-eyed stare from behind a black patch. Shutting one eye often signifies an ambivalent state in which one eye is looking, and the other would rather not see. This is a state of self-restraint out of choice, of partial sight.

The last part of the show presents a door peephole, the early image from which this body of work has grown. This simple, almost trivial image of a front door with a hole in it, within the syntactical progression of the show, creates a fascinating associative range. The peephole works both ways: it sees and is being seen, demands to be looked at with one eye only. It is the lens of the camera, the pupil of the eye, a sight.

In Alfred Hitchcock's movie Back Window Jack, a recuperating photojournalist, watches his neighbors from the building opposite his own. They open their windows in the summer heat, and he watches them through a camera with telephoto lens. In Michael Powell's Peeping Tom a serial killer uses a home movie camera to document the women he is killing. He closes one eye to film and opens the other to kill. And of course, there's the fashion photographer in Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup, who believes he has captured a murder on his camera, but fails in his attempts to incriminate the murderer.

In the 20th century, the camera had become predatory, metaphorically but often actually too. But the work here, in contrast to the violence customarily displayed in such cases, presents not a moment of violence, sexuality, or image of absence. However, the potential for violence is embedded in the images, very much present and ready to burst.